The NHS post-Brexit – a case for special treatment.

The future make-up of the NHS’s workforce has become a subject for much debate since the UK voted to leave the European Union in June’s referendum.

And there have been calls for it to be treated as a special case when it comes to recruiting abroad.

Independent fact checking organisation Full Fact reveals immigrants from EU countries other than the UK make up about 5% of the NHS’s staff in England at present – that’s around 55,000 employees.

Whilst senior politicians have indicated that those EU nationals already living and working here won’t be asked to leave – although even then it could depend on how long they have been here – nothing is set in stone and the fact is that the circumstances by which they came to be here – free movement of labour across European Union borders – will no longer apply in the UK once the process of leaving the ‘common market’ is initiated.

This at the very least is likely to make many of those European NHS staffers feel uncertain and unwelcome.

Simon Stevens, CEO of NHS England, has called for “early reassurance to international NHS employees about their continued welcome in this country”.

There are fears that without such reassurance many EU nationals will choose to leave the NHS to work in a country which makes them more welcome.

That’s an outcome which would be both tragic in terms of the UK’s reputation but also hugely damaging to the NHS, an organisation which is comfortably one of the world’s ten largest employers (the UK workforce is around 1.7m with 1.2m of those in England).

The NHS is already facing staff shortages in crucial areas and can’t afford to let talent drift away.

Because, have no doubt about it, talent is what we are talking about. Discussions around economic migrants during the referendum debate at times seemed to suggest that the UK is something of a dumping ground for foreign workers with little or no skill.

In the case of the NHS this is assuredly not the case. The non-UK EU citizens working in the NHS in England make up 10% of registered doctors and 4% of registered nurses (figures from the Health and Social Care Information Centre).

They also provide significant numbers of pharmacists, paramedics, support workers and administrative staff.

Restrictions on non-EU immigrants have affected NHS recruitment and the Brexit barrier to future EU member country recruits will only make matters worse.

Ensuring that those European NHS employees already here don’t start packing their bags in search of more welcoming climes must be seen as a priority.

So there in a nutshell is the NHS’s staffing problem post-Brexit vote: Restrictions on EU nationals coming to work in the UK will only add to potential skills shortages throughout the organisation while the 55,000 EU workers already employed by the NHS may feel their position here is a precarious one and act accordingly.

What then is to be done?

Well, that large group of NHS employees from Europe needs to hear from the organisation itself and from the Government and country at large how valued they are.

They need to know that they can stay in this country and build lives and careers for themselves here and not be seen as second class citizens.

But such reassurance is only likely to come after talks between the Government and the EU because the UK will be seeking reciprocal agreements surrounding the future of British workers in EU member states.

More generally, the rhetoric around foreign workers in the UK has to be a lot more positive going forwards than it has been in recent months.

NHS England medical director Professor Sir Bruce Keogh told the Health Service Journal that NHS workers from Europe must be made to feel welcome.

“If you are a European doctor or nurse you might not feel too welcome at the moment,” he said.

“The essence of delivering high quality care is dependent on a workforce that feels valued and secure.”

Such reassurances will certainly need to be made to any foreign workers recruited into the NHS from the EU in the future – and that remains a highly questionable scenario at present – as well as from further afield.

Future recruitment strategies will need to focus on the inclusiveness of the NHS as an organisation.

Writing not long before his death in 2014, and after extensive hospital treatment, the respected Labour politician Tony Benn said that as one of the few people left who had sat in Parliament with Aneurin Bevan – the Labour politician who established the NHS in the 1940s – it was extraordinary to see it functioning so well at close hand.

After remarking on the “absolutely perfect care for patients,” he had observed, he remarked that “80 per cent of the staff at {London hospitals} Guy’s and St Martin’s are non-white. It is a world community and I like that”.

It is this ‘world community’ aspect of the NHS that needs to be reinforced to provide support to existing foreign workers and to attract the essential employees of the future.

Kate Ling, senior policy manager at the NHS Confederation’s European Office in Brussels, speaking soon after the referendum result was announced, said:

“I know how worried many people are at the moment, with anecdotal evidence of EU staff uncertain about their future and NHS employers concerned they will have trouble recruiting to fill much-needed vacancies.

“We can all play a part in dispelling some of these fears by joining the #LoveOurEUStaff social media campaign, spearheaded by NHS Employers – we need to use every means at our disposal to spread the message that we welcome the great contribution that EU citizens make to our workforce.”

Ling admits, though, that at a practical level, much will depend on negotiations between the UK and its former European partners.

“The critical factor is whether or not the UK continues to have access to the single market, entailing freedom of movement for EU citizens to live and work in the UK and vice-versa, and requiring buy-in to EU employment and other legislation – the so-called ‘Norwegian option’.

“Under this scenario, virtually nothing would change for employers and staff.

“At the other extreme, a total exit from the single market would leave the UK completely free to determine its own policies on employment issues such as immigration, professional regulation, employment law and health and safety laws.”

Optimistically, though, she takes the view that it is unlikely that a future government would make it difficult for the NHS to recruit and retain the staff it needs.

“Britain could unilaterally decide to relax entry restrictions for certain groups of workers in shortage occupations and make it easy for them to stay, in the same way as Australia uses a points system to actively encourage entry by healthcare workers,” she suggests.

“The NHS Confederation and NHS Employers will actively push for a thorough review of the migration system so that employers can recruit and retain European staff with confidence.”

It is a rallying cry that is likely to increase in volume as the crucial talks surrounding the UK’s future relationship with the EU approach.

As ever, NHS recruiters will be charged with filling existing gaps and any enhanced shortfall in staff numbers resulting from the Brexit decision.

To do so they will need the help of those skilled in creating effective NHS recruitment campaigns against a backdrop of adversity.

One Black Bear has a history of working with the NHS, delivering multiple campaigns for various facets of the organisation over the past eight years.

Such experience is likely to prove vital in the months and years ahead.

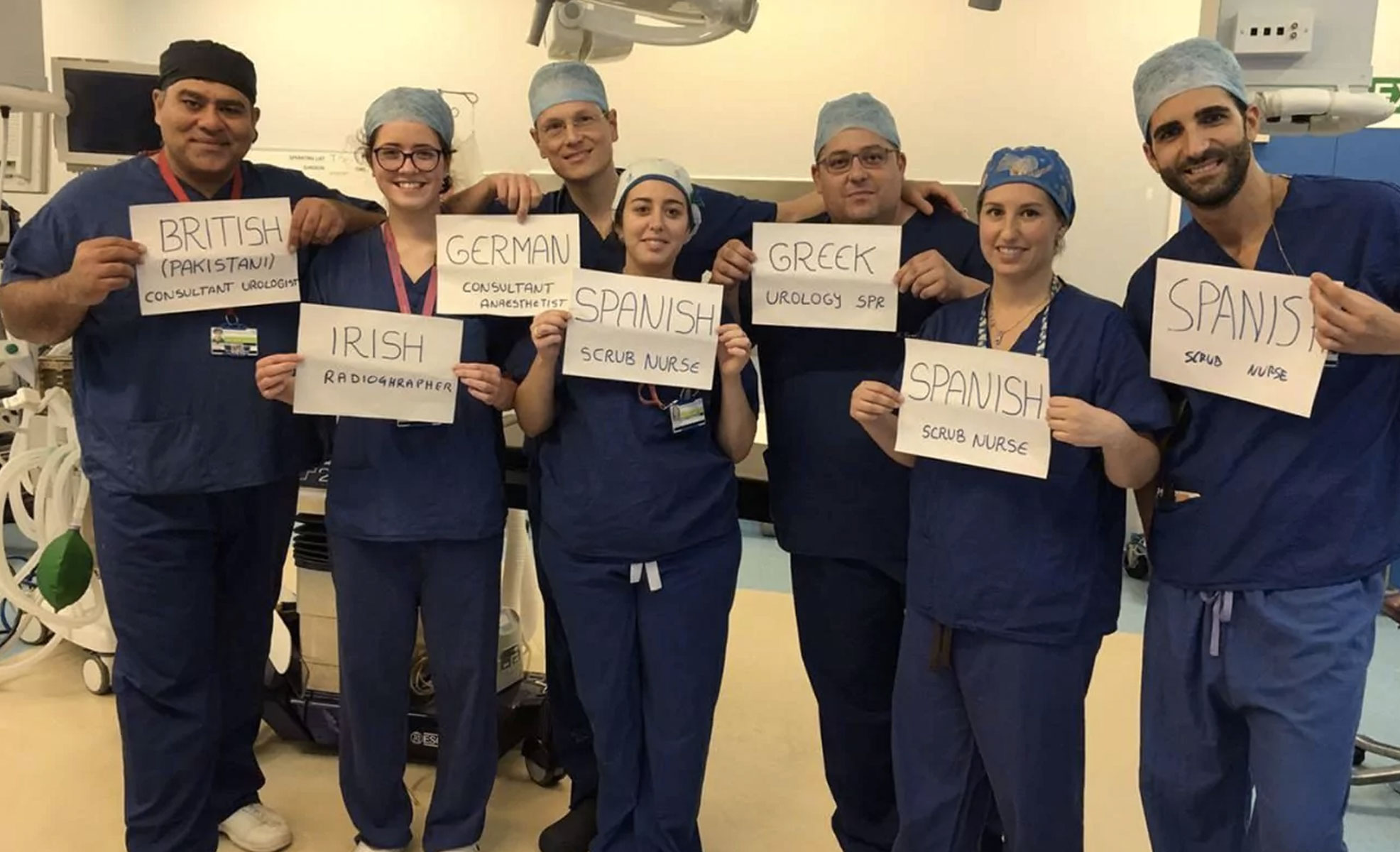

Photograph: Junaid Masood/PA